Chuck Berry, rock ‘n roll pioneer. Charlie Chaplin, Hollywood star. Frank Lloyd Wright, trailblazing architect. Jack Johnson, world heavyweight boxing champion. Besides sharing being household names, these four 20th-century icons share a shadier distinction. All ran afoul of one of the most misused and notorious criminal statutes to appear in the U.S. Code: the Mann Act.

The progressive America of the early 1900s saw sex for hire as a tentacle of an insidious vice trust. This conspiracy, popular thought went, recalled press gangs that once preyed on sailors. Instead of forcing men to serve aboard ship, the theory held, vice lords employed liquor, trickery, and violence to lure women into brothels and hold them there as toys for men. The popular term for sex workers was “white slaves,” initially used by 19th century Caucasian industrial workers to describe life on the factory line.

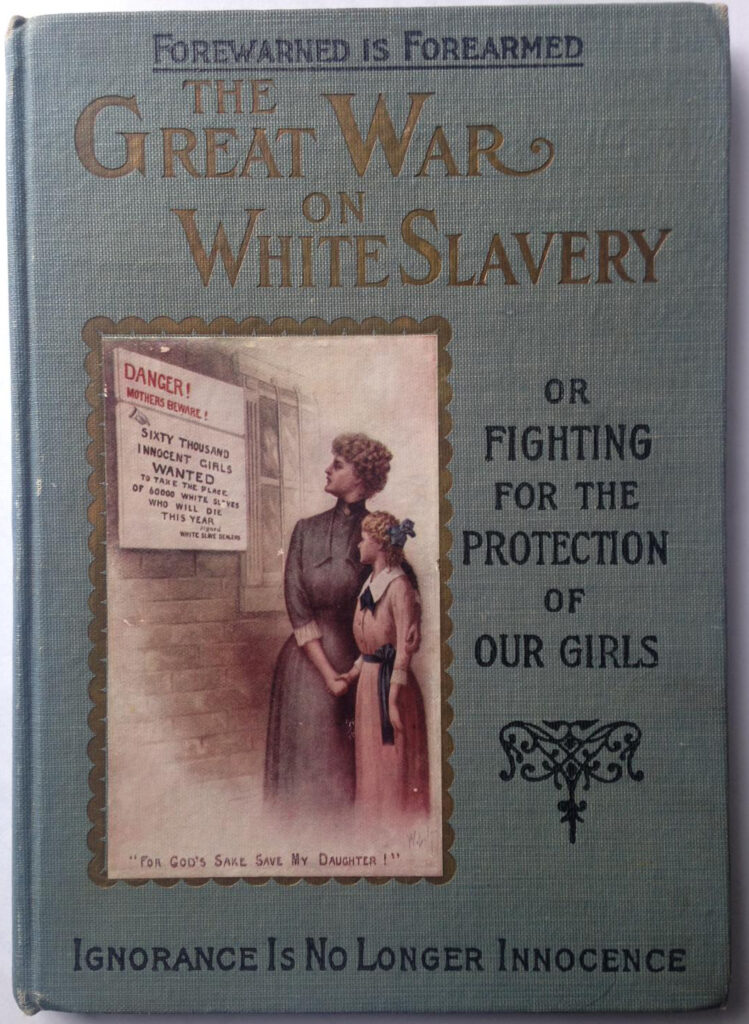

In 1907, muckraker George Kibbe Turner claimed in McClure’s Magazine that the “keepers of the regular houses of ill-fame have private arrangements with men, who ruin young girls for their use.” Turner described a network active in Boston, New York, Chicago, and New Orleans that sold young women for $50 a head. Chicago prosecutor Clifford G. Roe wrote a book, The Great War on White Slavery: Fighting for the Protection of Our Girls, billed as “the official weapon of this great crusade.” Reformer Ernest A. Bell published War on the White Slave Trade: A Book Designed to Awaken the Sleeping and to Protect the Innocent; the cover showed a mother weeping at the vacant bed of a daughter gone wrong. A turn-of-the-century federal investigation claimed that women prostituted themselves because of men “in the business of procuring women for that purpose—men whose sole means of livelihood is the money received from the sale and exploitation of women.” The white slavery scare dovetailed with Victorian morality, which cast women as wives and mothers, viewed only a chaste woman as a suitable wife, and questioned a woman’s ability to resist a sweet-talking man.

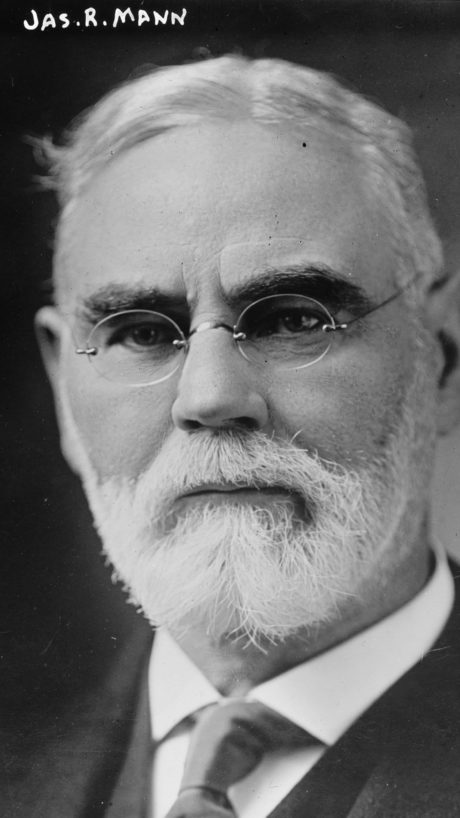

State laws were seen as ineffective; Congress decided to act. Point man was Representative James R. Mann (R-Illinois), 53, whose district was vice-ridden Chicago. A House member since 1897, he displayed fierce independence. To a GOP elder’s reproach for voting with Democrats during his freshman term, Mann snarled, “I shall always vote as I damn please.” He had earned his progressive stripes by sponsoring the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which swept drugstore shelves of many narcotics-laden patent medicines and laid the foundation for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

On December 6, 1909, Mann introduced H.R. 12315, the White Slave Traffic Act, to make it a felony to take across state lines “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” Mann, whose name quickly attached itself to the measure, was gunning for organized procurement rings. His bill was designed, the Senate Commerce Committee said, “solely to prevent panderers and procurers from compelling thousands of women and girls against their will and desire to enter and continue in a life of prostitution.”

However worthy its intent, the Mann Act was imprecise. Nothing in the bill’s language limited its application to commercial sex, organized procurement, or rape. The bill left undefined the inflammatory but vague terms “debauchery” and “immoral purpose.” The wording, broad enough to encompass sex between consenting adults, created a danger of selective enforcement. About the only specific term in the bill was a stipulation limiting prosecution to instances in which state lines were crossed—because Congress had jurisdiction only over interstate commerce.

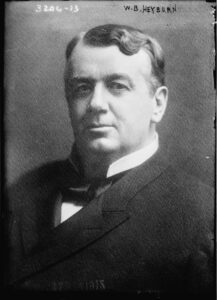

Three congressmen warned colleagues they were marching into a swamp. Rep. Harry A. Richardson (R-Delaware) called Mann’s bill “impracticable, vague, indistinct, and indefinite in every respect.” Rep. William C. Adamson (D-Georgia) predicted “a wide field of different opinion as to who was vile and impure and what practices constituted immorality.” Rep. Weldon B. Heyburn (R-Idaho) said he feared the wording could ensnare a railroad conductor whose train carried a prostitute from state to state.

Moral outrage triumphed. The bill was necessary, said Representative Thetus W. Sims (D-Tennessee), to prevent “the taking away by fraud or violence from some doting mother or loving father, of some blue-eyed girl and immersing her in dens of infamy.” Imagining women being “drugged, debauched, and ruined,” Sims said he could not picture what would “justify a civilized man in voting against this bill.” Rep. Edward W. Saunders (D-Virginia) called the white-slave trade “a blot on modern civilization, but the extent to which our supineness has allowed it to proceed, is the crowning disgrace of the twentieth century.” The House passed the bill on January 26, 1910. Senate passage followed on June 25 and President William Howard Taft signed it that day. The Mann Act was law.

The ink had barely dried when, three days later, a New York grand jury that had been convened to analyze the white-slave trade reported finding no evidence of “any organization or organizations, incorporated or otherwise, engaged as such in the traffic in women for immoral purposes.” Muckraker Turner, who had labeled New York City a “leading center of the white slave trade,” admitted to jurors that his articles had been “overstated and deceiving.” The New York Times disdained claims of white slavery rampant as “a figment of imaginative fly-gobblers.”

Even so, calls rang out to enforce the new statute. U.S. Attorney General George W. Wickersham, urging restraint, said he would “refrain from instituting technical or trivial cases” and limit prosecutions to bona-fide white-slave operations. In two years, federal prosecutors got 337 Mann Act convictions, mostly in cases brought against men. Gradually, headline-hunting prosecutors came to see in a loosely written statute and unavoidably salacious coverage a reason to pursue cases against individuals well known and outside the mainstream.

Jack Johnson, who in 1908 had become boxing’s first African American heavyweight champion, was the first celebrity to get a Mann Act going-over. For the headstrong Johnson, “no law or custom, no person white or black, male or female—could keep him for long from whatever he wanted,” wrote biographer Geoffrey C. Ward. Flamboyant and outspoken, the ebulliently black Johnson inspired Caucasian cries for a “Great White Hope” to put him in his place. Boxing had enriched Johnson, whose offense was to think that he should be able to behave as badly as any wealthy white man. In 1912, Johnson, 34, traveled with and bedded Lucille Cameron, 19, a Caucasian. Cameron’s mother, saying she would rather see Lucille in jail than spend “one day in the company of that negro,” blew the whistle. Agents of the U.S. Bureau of Investigation, forerunner of the FBI, arrested Johnson in Chicago. “Negro Pugilist Charged with Abduction of 19-Year-Old White Girl,” a Times headline blared. Cameron refused to cooperate and the case crumbled. Later that year, after she and Johnson wed, an outraged Rep. Seaborn Roddenberry (D-Georgia) proposed a constitutional ban on interracial marriage.

The Bureau of Investigation persisted, soon enlisting another Johnson paramour as a witness for the prosecution.Belle Schreiber, 23, according to the press a “manicure girl and burlesque queen,” testified against her former lover, helping to get him indicted for a 1910 jaunt that took the pair from Pittsburgh to Chicago, while presumably engaging in coitus. Johnson, confident of acquittal, claimed never to have taken Schreiber anywhere, noting besides that consensual sex between adults was legal. The boxer’s certainty evaporated on May 13, 1913, when a clerk in the U.S. District Court in Chicago read the jury’s guilty verdict. The court sentenced Johnson to a year and a day in federal prison. Released on appeal, Johnson, with Cameron–his “white wife,” the Times took care to remind readers—fled to Canada, then to Europe. The exiled Johnson lost his heavyweight crown to white hope Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba, in 1915. Johnson surrendered to U.S. authorities in 1920 and served his time.

The Mann Act’s Commerce Clause-driven focus on interstate travel brought incongruous results. “A village Don Juan may misbehave with all the willing dames in his parish, and then scatter his seed in every other county in the State, with no other punishment than the remorse of contraband pleasure,” the American Mercury noted. “But an occasional sinner who escorts a fair partner into a neighboring commonwealth with fornicative intent, is condemned to several years of sexless confinement.”

“Immoral purpose” was a malleable term, and federal courts disagreed on whether under the Mann Act that intent extended to non-commercial sex. A test case soon arose. In 1913, Drew Caminetti, 27, and Maury Diggs, 26, were longtime pals and local celebrities in Sacramento, California. Caminetti’s father, Anthony, recently had accepted a nomination by President Woodrow Wilson to head the U.S. Bureau of Immigration. Diggs had served as California’s state architect. The two men, each married with families, began running around with Lola Norris, 19, and Marsha Warrington, 20. Diggs and Caminetti took their companions to Reno, Nevada, supposedly promising to obtain divorces and marry the women. Tipped off, perhaps by a spouse, police surprised the couples on March 14, 1913, at a cottage in Reno the men had rented under assumed names and arrested Diggs and Caminetti.

The case bore no hint of commerce. The indictment charged only that Caminetti and Diggs had intended to make each woman “his mistress and concubine.” In September 1913, a jury found both guilty of Mann Act violations. “If I am a white slaver, 90 percent of the men living are as guilty as I am,” Diggs said. The act’s author had no patience for those who objected to making philandering a felony. “I shed my tears for those who have been led astray, who have been debauched through fear and force,” Mann thundered. “I shed my tears in behalf of the innocent.” Diggs, considered the brains of the operation, drew two years in prison; Caminetti, 18 months. Each later divorced, and Diggs married Warrington. Appealing their convictions to the U.S. Supreme Court, Caminetti and Diggs argued that the act covered only “the traffic in women for gain,” not unpaid adultery. The Court decided by a 5-3 vote that the act covered both. To limit Mann Act enforcement to commercial vice, the majority asserted, “would shock the common understanding of what constitutes an immoral purpose.” The three dissenting justices voiced fear that blackmailers would use “the terrors of the construction now sanctioned by this court as a help—indeed, the means—for their brigandage.”

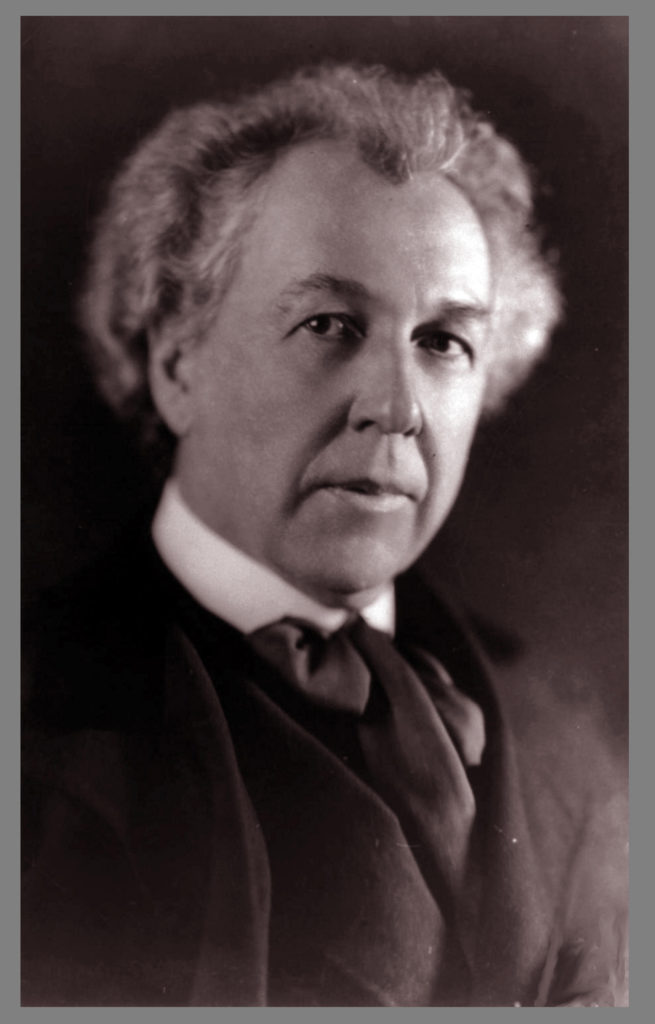

The Mann Act next ensnared architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose private life had become a spectacle. “Genius that he is in his chosen profession,” the Twin City Reporter noted, “his life so far as the married side is concerned has been one blunder after another.” In 1924, separated from second wife Miriam Noel, Wright, 57, met Olgivanna Milanov, 26. Within a year, Milanov, a ballet dancer, was living with Wright in Wisconsin. The couple had a child. Noel sued Wright seeking separate-maintenance payments, and Milanov for alienation of affection. Wright’s finances were jumbled, and creditors were circling. He and Milanov fled Wisconsin to a cottage near Lake Minnetonka, Minnesota, that they rented as Mr. and Mrs. Frank Richardson. Noel persuaded police to arrest the couple there on Mann Act charges. Lafayette French Jr., the U.S. attorney for Minnesota, declined prosecution, but Noel got her alimony and, Wright bitterly observed, “the ruination she had planned and wrought by the false, sentimental appeal of ‘outraged wife.’” Wright wed Milanov in 1928.

Not all Mann Act cases were vindictive or misdirected. In 1916, the Justice Department reported using the act to put out of business an unnamed individual “known as the ‘boss of the underworld’ in one of the largest cities in the United States.” Non-commercial prosecutions proved knotty, given the statute’s broad discretionary powers. Prosecutors tried to avoid bringing cases whose only factor was extramarital sex, but whatever cases they brought tended to have an extra helping of the lurid or unseemly.

In April 1918, police arrested a 55-year-old University of Chicago professor for dallying with a woman, 24, whose husband was fighting in France. After her husband shipped out, the woman said, the academic had been “most solicitous for my comfort.” Federal prosecutors dropped the Mann Act case. Local charges still applied, but a municipal judge acquitted the professor. He lost his teaching job. His wife took him back, calling him “a foolish boy.” The soldier and his wife divorced.

In July 1937, authorities in Los Angeles prosecuted John Wuest Hunt, 33, an evangelical cult leader, for luring a juvenile follower across state lines to have sex. “Mr. Hunt told me I was to be the mother of the new redeemer of the world,” the girl testified. “It was to be an immaculate conception.” Hunt was sentenced to three years in prison.

As predicted, the Mann Act did enable abusive prosecution. In 1941, movie star and director Charlie Chaplin, 52, met Joan Barry, 22. Chaplin, a prominent liberal and British sleeping together. In October 1942, to participate in a New York rally sponsored by the Artists Front to Win the War, Chaplin traveled from California with Barry. At the rally at Carnegie Hall, Chaplin gave a pro-Soviet speech. The FBI, which viewed the rally’s sponsor as communistic, invoked Chaplin’s 23-day sojourn with Barry to bring a Mann Act case, threatening Chaplin with not only prison but deportation. At trial in Los Angeles, the director denied any intimacy with Barry on the road. Jurors acquitted him. Courtroom spectators applauded.

Victory brought Chaplin no pleasure. He felt “empty, hurt and denuded of character,” he said. Calling the charges a “bogus piece of legal opportunism,” Chaplin claimed to have heard from U.S. Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy at a dinner party that an unnamed high-ranking official was out to get him. Indeed, an internal FBI memorandum dated August 26, 1943, quotes FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover as saying that the government should “vigorously” pursue the Mann Act case against Chaplin.

World War II loosened American attitudes toward sexuality, and afterwards Mann Act prosecutions lost favor. Underpinned as it was by assumptions about society having to protect women from themselves, the act became a relic. But its teeth remained sharp.

Nella Bogart, 32, was charged under the act in 1957 for sending two prostitutes from Manhattan to Newark, New Jersey, to “entertain” at a convention. When Bogart’s defense attorney pointed at the men who had hired her to supply the prostitutes and noted that none had been charged, the all-male jury acquitted the self-described call girl in less than an hour.

A case brought against the entertainer Chuck Berry combined the act’s animating spirit and a legitimate violation.In 1959, Berry, an African-American pioneer of rock’n’roll, was touring the southwest United States, steering his Cadillac from town to town to perform “Maybellene,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Johnny B. Goode,” and his other hits. That December 1, in El Paso, Texas, Berry, 33, met and hit it off with a Native American girl who had quit school after the 8th grade. Promising the 14-year-old a job checking hats at his St. Louis, Missouri, nightclub, Berry took her across several states as he completed his tour. They stayed together, registering at as Mr. and Mrs. Janet Johnson, copulating in their motel rooms and in the backseat of Berry’s red Cadillac, she claimed later. Berry did put his new friend to work at his club, but on December 18 he fired her, took her to a bus station, bought her a ticket home to El Paso, and said goodbye. She complained to authorities, who charged the married Berry under the Mann Act. At trial in federal court in St. Louis, Berry denied having had sex with the girl, claiming he had hired her only out of charity—but his testimony, biographer Bruce Pegg noted, was evasive and deceptive. The trial judge constantly mentioned Berry’s race. On March 4, 1960, jurors convicted the musician, a decision reversed on appeal based on the trial judge’s behavior. In March 1961, a different judge reheard the case. Convicted again, Berry served a year and a half in federal prison.

The sexual revolution and the women’s movement pushed the Mann Act even more out of step with American society. By the late 1960s, prosecutors were bringing fewer than 100 cases a year, but the Mann Act stayed on the books until 1986, when Congress amended the old statute and wove the update into the Child Sexual Abuse and Pornography Act. The goal, said sponsor Rep. William J. Hughes (D-New Jersey) was “to modernize the offenses and to make them gender neutral.” Vague terms like “debauchery” and “immoral purpose” got the boot, and criminality no longer hinged on any one person’s definition of morality. The act now covers the transport of males and females. Still known informally as the Mann Act, 18 USC §2421 now applies only to interstate travel for the purpose of prostitution or “any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense.” No longer need consenting adults engaging in non-commercial, non-criminal sex fear the Mann Act, which now focuses on its original purpose, human trafficking, thanks to revisions made decades too late for the amateur philanderers arrested, prosecuted, and terrorized under a statute never intended for them in the first place.